The age of overcapacity

Overcapacity and falling freight rates spell trouble for the future of the shipping industry, but are government policies adding more confusion to the mix?

Public policies – and pro-cyclical policies in particular – might be creating more problems than they solve when it comes to dealing with overcapacity in the shipping industry, according to Olaf Merk, ports and shipping administrator for International Transport Forum at the OECD.

Policies to artificially inflate the capacity of the shipbuilding sector, to tolerate the substandard scrapping of ships and to muddy links between new port capacity cargo flows are just some of the many policies Mr Merk believes need to be reassessed in order to mitigate the effects of overcapacity, and in doing so create a more sustainable and profitable future that is in the collective interest. He dismissed arguments that overcapacity is in the collective interest: lower freight rates caused by overcapacity mean that consumers are getting goods at lower prices because maritime transport costs are lower, “but not if the rates are so low that shipping doesn’t have a sustainable, profitable future”.

Overcapacity can also lead to more market concentration, adds Mr Merk, to such an extent that the rates will actually go up after that situation has become clearer. Further, “it is not in the collective interest if it compromises the service that is given to shippers”, he says.

It could also be argued that ship replacement could improve the sector’s sustainability; you could get more sustainable and modern ships at better rates because of overcapacity.

“Finding ways to mitigate overcapacity is, in my view, a way to support what makes the maritime industry and maritime transport really indispensable and relevant.”

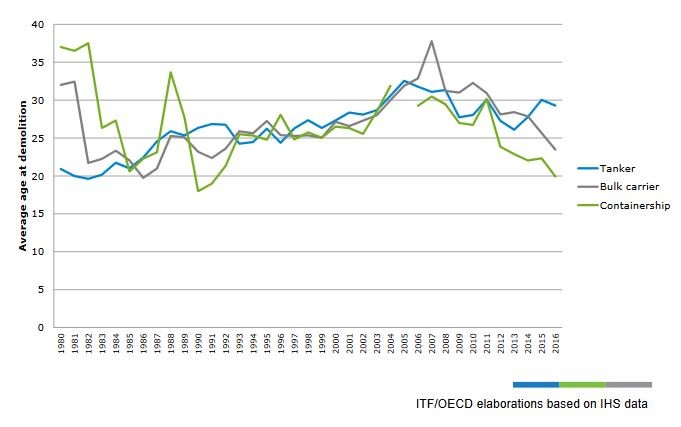

Again this might be true, says Mr Merk, but not if the average scrapping age becomes so low that perfectly efficient ships are being scrapped, which is a question you might ask if you are approaching scrapping ages of sub 20 years. “There is nothing sustainable about scrapping a perfectly functional ship,” he says.

Assessing the collective interest

On the flipside, Mr Merk says there are more dominant arguments to confirm that overcapacity is not in the collective interest. One is about government money into the shipping sector and related sectors, state aid, favourable tax treatment, and onboard and land infrastructure that might be related to the behaviour of shipping companies. “There is a financial interest and it is being used to build capacity that isn’t actually used, it’s an inefficient use of public money,” he says.

Next, is the issue of volatility. “Nobody actually benefits from the volatility of the supply chain and shipping sector except from maybe traders,” says Mr Merk. “Ideally, you’d like to have a supply chain that is fairly stable and has no disruptions, where every company can focus its energy on providing better service to clients and long-term thinking instead of being occupied thinking about whether it will survive the next quarter.”

The third argument is about the systemic risk of overcapacity in the shipping sector, “which is basically to say that if shipping suffers other sectors might also suffer”, explains Mr Merk.

“This can become problematic,” he continues. “An example is shipping loans. A lot of ships and shipping owners are financed by the banking sector so if it has a lot of overcapacity, this immediately has an impact on shipping loans, banks and the financial sectors. The risk of overcapacity in shipping sector could spread out over the whole supply chain.”

Addressing the question of what can be done to solve the issue of overcapacity, Mr Merk says shipping companies are already taking action, ordering less, cancelling orders, scrapping more, lowering speeds and laying-up vessels. “There are a lot of strategies that are being deployed to realise lower capacity,” he says.

However, this presents its own challenges: “In a way this is challenging because every company is acting individually so there might be some companies sitting this one out and doing nothing knowing that others might actually scrap vessels of their own to solve the problem.”

The problem with policies

The situation is being made worse by certain public policies, says Mr Merk. In particular, he argues that pro-cyclical policies have a habit of making good times better and bad times even worse.

“An example of this is the pro-cyclical support for shipbuilding that we have seen in some nations where the states seem to have put more support in the sector to actually keep the capacity of the shipbuilding sector going which of course has had a peculiar effect on the shipping sector,” he says. “Similar can be said for the support for shipping, and also about the way substandard scrapping of ships is tolerated.”

One idea to mitigate the effects of overcapacity through government policy is to reassess state aid to shipping, shipbuilding and ship finance. “It could be we need a clearer link between new port capacity cargo flows,” suggests Mr Merk. “For example, only invest if you have the commitment of shipping to actually use infrastructure.”

Government policy could also address volatility: Mr Merk puts forward the idea to only allow support to the shipbuilding sector that is at the same time connected to a reduction of that shipbuilding capacity. For example, he says: “The support could be in the resources instead of keeping an existing shipbuilding capacity in place.”

Another idea is to look at the way shipping is taxed, adds Mr Merk. “New forms of taxes such as the carbon tax could help to make taxation streams from shipping more cyclical and in a way mitigate some of the volatility of the shipping cycle.

“Another idea that has been proposed is a speed limit for ships which could be made variable according to the state of overcapacity in a certain sector or subsector in shipping.”

With regard to the systemic risk, Mr Merk suggests limiting the financial leverage of the sector, reassessing the limits of the vertical integration of the shipping sector with other sectors, and restricting the use of substandard scrapping.

“Finding ways to mitigate overcapacity is, in my view, a way to support what makes the maritime industry and maritime transport really indispensable and relevant.”