Contractual chaos of emissions regs

Reduction measures ‘counterintuitive’ in commercial terms

By Carly Fields

Is there a misalignment between incentives to improve carbon intensity? That was the question posed by Alessio Sbraga, a partner in HFW’s shipping department in London, at a recent joint Baltic Exchange and Institute of Chartered Shipbrokers webinar.

Sbraga told attendees that the commercial consequences of emission reduction measures such as the Energy Efficiency Existing Ship Index (EEXI) and the Carbon Intensity Indicator (CII) are “counterintuitive”.

In his presentation, Sbraga gave a snapshot of the anticipated impact of the EEXI and CII regulations on contracts and the disputes landscape going forward. He noted that the impact is expected to be “most profound” on charterparty contracts.

EEXI is a technical measure aimed at improving energy efficiency of the existing design of vessels and consequently reducing the energy output of existing vessels. The CII is an operational requirement used to measure the carbon intensity of the commercial activities of a vessel on an annual basis.

“It's vital to have a basic understanding of what these requirements amount to in order to understand the potential contractual disputes landscape,” Sbraga said.

He described CII as “complicated and contractually invasive for commercial parties”. Under CII, a vessel’s carbon intensity will be generated with an annual CII rating from A to E. A ‘C’ rating is effectively the minimum required, while a vessel rated ‘D’ for three consecutive years, or rated ‘E’ in any single year, will be required to develop a plan of corrective action to achieve CII compliance.

Achieving the CII target is not expected to be straightforward and will likely require vessels to change the way they operate to be more efficient, but not necessarily commercially efficient. “What this means is that it's very likely that operational adjustments in real time to the vessel’s commercial operation will be required,” Sbraga said. Examples of these adjustments include reducing speed, reducing cargo volume intake, increasing distance sailed or deviating from the shortest or quickest route.

He described CII as “complicated and contractually invasive for commercial parties”.

Cutting though rights

A criticism of the CII is that it can be improved on longer distances with lighter loads, which has commercial implications. “The carbon intensity of the vessel is heavily dependent on the way in which that vessel was traded and also on external factors outside of both parties’ control, which can impact the vessel’s consumption and emissions.” This could include bad weather conditions and prolonged port stays in tropical waters – which can both have a profound effect.

“The real crux of the problem here is that ongoing CII compliance has the potential to cut through the very heart of a time charter and all the fundamental rights held by time charterers,” Sbraga said. CII compliance is especially problematic in a contractual context, because following a time charterer’s orders will have a direct impact on the carbon intensity, he added. Any preventative steps – for example, slow steaming, deviating, or reducing cargo intake - would place the owners in breach of the traditional charter obligations such as due dispatch, employment orders, speeding consumption, and warranties.

In some cases, these breaches will result in claims for damages, as opposed to create a right to termination, Sbraga said. In more sophisticated charters the consequences could be more severe. “While there may be defences which owners can try and employ here, justifying that preventative steps need to be taken at the material time is likely to be complicated for the owner from a causation perspective.”

“The real crux of the problem here is that ongoing CII compliance has the potential to cut through the very heart of a time charter and all the fundamental rights held by time charterers,” Sbraga said.

Complicating factors

EEXI, meanwhile, is likely to require technical modifications which are specific to that vessel – for example, energy power limitation (EPL) devices – and experience demonstrates that non-routine technical modifications mandated by international regulations can be problematic with regards to contracts.

Sbraga noted that while primary responsibility for MARPOL compliance traditionally rests with owners by virtue of the vessel’s flag or their maintenance obligations under a time charter contract, for EEXI there are likely to be two additional complicating factors. “First, the EEXI regulations do not prescribe what type of modifications are required; the energy efficiency benchmark simply has to be met. Where incorporated, compulsory modification clauses or the like could be triggered, but this will be entirely dependent on the particular wording of the clause used. Where such clauses do not apply then reviewing off-hire, loss of time, and drydocking clauses will be important to allocate the time, risk and cost involved.”

Secondly, Sbraga noted, depending on the type of technical modification implemented, this may also impact the future performance of a vessel as the vessel may no longer be technically or physically able to perform in the same way. “This will be problematic,” he said. “Logical amendments to the technical description, questionnaires, and even speed and consumption warranties are likely to be required. In fact, this is what the market is seeing with EPLs and care has to be taken to review existing speed and consumption warranties which warrant maximum speeds.” There will likely be no unilateral right to amend an existing contract in this way, so this is expected to be a source of dispute, he added.

Specific clauses, such as BIMCO’s EEXI transitional clause, are helpful, but there is no one-size-fits-all solution because that will depend on the type of modification used, the ship’s trade, and also the existing contractual provisions.

Time charterers should not think that they can sit back and ride this out, Sbraga said, as these regulations will almost certainly lead to disputes and commercial conflict.

There will likely be no unilateral right to amend an existing contract in this way, so this is expected to be a source of dispute, he added.

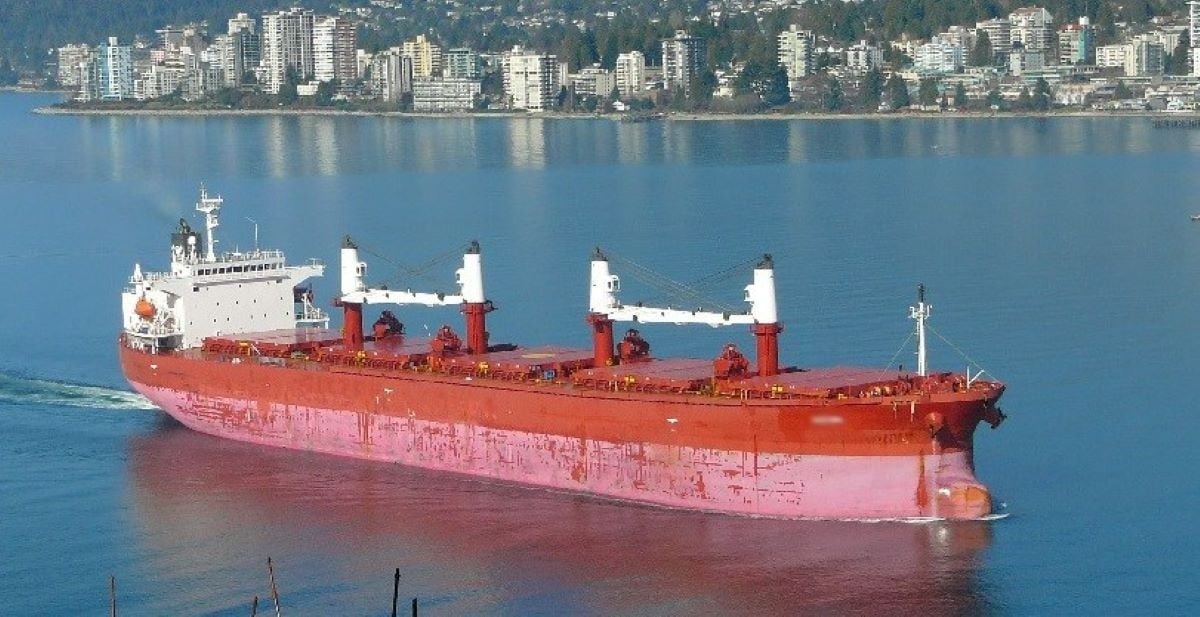

Caption: Incoming regulations will lead to a rise in legal disputes. Credit: pdufour, freeimages.com